History of the Barony of Otterinverane

In Cowal, on the eastern shore of Loch Fyne stands the Barony of Otterinverane, or colloquially “Otter”. This area takes its name from the sandbank which juts out more than halfway across Loch Fyne, ‘An Otir’ meaning “the long low promontory” in Gaelic. During the middle ages there was established a barony at Otter. In this time barons across Scotland were entrusted by the monarch to hold land for them and in return keep law and order, dispense justice and if necessary, raise men for war. At Otter the barony took its name from the promontory and was called Oitir an Bharain, meaning ‘the Baron’s Otter’.

The history of the Barony of Otterinverane is in many ways also the history of the Cowal peninsula, of Argyll, and even of Scotland itself. The Barony has helped to shape the local history of the area, and at times the development of the Scottish Nation. To tell the story of this Barony we must begin in prehistory, long before a written record and where our only evidence is that left beneath the ground. The neighbourhood that is Argyll has been in human occupation since prehistoric times, and we tell here the story of the Barony of Otterinverane from the first evidence of settlement in Cowal through the centuries. For most of history we can only get a sense of what was happening in the area, catching brief glimpses in the historical record when Cowal and Otter were part of larger events. Later, the Gaelic families of Argyll can be seen in possession of Otter during the middle ages, as it became an important site and eventually the stronghold of the MacEwen clan. In the later middle ages it was acquired by the Campbells of Lochow who became Earls and then Dukes of Argyll. Along with many lands in Argyll they held the Barony of Otterinverane almost without break for five hundred years. Today, Otterinverane continues to be held by a Baron who is the direct lineal descendant of numerous prior Otterinverane barons and who also shares common ancestry with all previous holders of the Barony throughout its long history, including numerous Monarchs.

Prehistory

The landscape of Argyll has little changed throughout the millennia and the visitor today can easily imagine how the first humans to set foot in its forests and row along its waterways might have seen this land. Argyll has historically been the heartland of Western Scotland, a place where the Highlands meet the sea. The broken shoreline of Argyll, with its hills, islands and inlets has drawn in invaders, settlers and travellers since time immemorial and continues to pull people in today. With one eye it looks inwards toward Scotland’s interior, with her mountains, muirs and forests. With the other eye Argyll looks out across the sea to Ireland, which ever since prehistory has been part of the same world, sharing people, culture and trade across the narrow water.

The Barony of Otter is in the Cowal peninsula, one of the constituent parts of Argyll. It is on the mainland which looks out toward the Firth of Clyde to the east, the isle of Bute to the south and Loch Fyne to the west. To the north you can take the land route to inner Argyll. Cowal has been inhabited for thousands of years, with humans following the retreating glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age. For these times only the evidence left in the ground remains, but from this we know Cowal has been occupied by humans since at least the early Neolithic period. At Ardnadam there is evidence of a settlement of five structures and perhaps a chambered tomb from this time. On the same site is evidence of a late Neolithic house and later were added postholes and a mound, probably in the Bronze Age, before we lastly have evidence of a collection of Iron Age roundhouses, enclosures and other structures. At Portavadie there is a cairn which is either late Neolithic or Bronze Age. Across the parish of Kilfinan, which occupies the western part of Cowal and includes the Barony of Otter, there are tall standing stones which would have been sites of importance to prehistoric people in Cowal.

The immediate area around Otter has been in occupation since at least the Bronze Age, which we know from a remarkable series of finds near Ballymore House, about a mile to the south of the present Otter Ferry landing. Here, a small stream flows out across the beach into Loch Fyne and when excavating an ornamental pond in the house’s garden several bronze objects were found. These were preserved in the house when in 1942 the archaeologist V. Gordon Childe visited the area and was invited by Captain MacRae, the owner, to see them. Intrigued, Childe suggested the bronzes be taken to the National Museum for treatment to help preserve and record them. Though corroded and broken, it could be made out that there were eight socketed celts, two leaf-shaped swords, seven spear-heads, and a corrugated bronze tube. Some of the spear-heads had been deformed and split lengthwise and in one spear-head was discovered a piece of wood that looked as though it had been forced into the socket, suggesting that they had all been broken before burial. This has been found to be common with similar Bronze and Iron Age hoards which contain broken objects. These are known as ‘founders’ hoards’ and were apparently deposited with the intention of being recovered at a later date, often containing both broken and complete objects. This was the first hoard, and the first accurately located late Bronze Age objects, to be reported from the eastern shore of Loch Fyne, and it is thought they originated from Ireland, showing the early connections across the sea. Late Bronze Age Scottish metalwork is often explained as the result of a combination of local development and Irish influence. It is in about this time that Celtic migrations were occurring into Scotland, and it is most likely that in Argyll these crossed from Ireland over the North Channel. The location of this group of bronzes, opposite Loch Gilp, is logical as this was one terminus of a well-known trade route from Crinan and the Sound of Jura. It was also not far from Tarbert, and the peninsula could also be crossed. Otter is also at the end of a difficult but ancient route, still followed by road, across the Cowal peninsula to Holy Loch and the Clyde estuary.

The Iron Age

What is now Scotland begins to step into written history in the late Iron Age with the Romans who recorded in writing for the first time the peoples of these lands. From these early recordings we get the name of the people who inhabited the area during the late Iron Age. The Attacotti tribe lived in the area from Loch Fyne in the west to the river Leven and Loch Lomond in the east. They were said to have taken their name from the British Eithacoeti, meaning ‘the men dwelling at the edge of the wood’. They were probably given this name by the northern Cumraig or Welsh peoples who neighboured them. It has been suggested that the Attacotti had colonised the area in the third century, coming across from Ireland. This would have made them one of the earliest groups of Scots to come and settle in northern Britain. On Ptolemy’s map of North Britain from the second century he did not identify the Attacotti but Richard of Cirencester, a fourteenth century monk, added them to a manuscript he had. Richard placed them to the north of the Firth of Clyde and in one of the first historians of Britain, Bede, believed a people he called the ‘Dalreudini’, or ‘Dalriatians’ lived in that region, saying the Scots had first arrived north of Alcuith, in what is now called Dumbarton Castle, and settled there. Riada was anciently believed to be the name of the leader of this first colony of Scots to come across from Ireland in the middle of the third century from which the Scots of Argyll would later take their name. It seems likely that the Attacotti were in fact the Scots who arrived from the north of Ireland during the third century, settling first the land of Dumbartonshire and Cowal between Loch Lomond and Loch Fyne, thus being the early “cradle” of what would become “Scotland”.

The furthest extent of the Roman Empire’s control in Britain was the Antonine Wall which ran to the Firth of Clyde, just to the south of where the Attacotti lived. This frontier was only maintained for a few years before it was withdrawn to Hadrian’s Wall. Though it was outside of Roman occupation, the area around the Barony of Otterinverane would have come into contact with the Roman world, through trade and warfare. At the time of the accession of Emperor Valentinian in the year 364 there was a period of increased attack on the Roman occupiers by several peoples. First were the Picts, second were the Attacotti from the shores of Dunbarton and Cowal, and third were the Scots who came from Ireland. The attacks of 364 were said to have been more destructive than any former incursion and this probably was because these tribes sensed the weakness of the Roman Empire.

It has long been thought there was a second colonisation of Irish Scots in the sixth century, possibly as early as the year 500, that settled in Argyll. This colony was said to have come under the leadership of three sons of Erc: called Fergus; Loarn; and Angus. Erc was then the King of Irish Dál Riata, an area which is in modern-day Antrim, Ireland around 470. He was said to be a descendant of Conaire Cóem ‘the beautiful’, who was High King of Ireland in the second century, who in turn was descended from the famous Érainn King Conaire Mór. This Irish King had ruled an area around county Cork and Kerry and according to legend was also High King and descended from a long line of Irish High Kings. The sons of Erc who came across from Ireland divided much of Argyll between them to rule. Fergus had a son Domangart Reti, who had two sons, Gabran who occupied Knapdale and Kintyre, and Comgall who occupied Cowal, possibly with a stronghold at Dunoon. It is from the Prince Comgall that Cowal is said to get its name.

These Irish-Scots chieftains and Royalty were part of a large exchange of peoples and culture who moved between these lands that later became known individually as Ireland and Scotland. It has been suggested that the dun at Kildonan, not far from the Mull of Kintyre, was likely one of the first to be settled by the Scots of Ireland, but their peoples and influence came across a large part of what is now Argyll. While we often focus on the unique histories and legends around the great leaders who ruled these lands and brought their followers back and forth across the sea, some historians believe we should picture instead a long period of exchange. There would have been many people trading, marrying, and fighting across the North Channel to what is now Western Scotland especially from the areas we now know as Down, Antrim, Derry, Donegal and Tyrone in Ireland. The evidence for these exchanges in the centuries around the year 500 is in the archaeology with similar types of high-status metalwork found in western Scotland and north-east Ireland including spear-butts and brooches as well as ceramics. It is important to know that this was a sea-based society, with most of Argyll linked by around a day’s sailing to Ireland. The linguistic evidence suggests a shared language and parts of a shared culture between the people of Northern Ireland and Western Scotland.

Dál Riata

The Annals of Ulster say that from 626 to 988 the Scots of Argyll were named for a man named Riada. This legendary ancestor may have been the legendary Scottish leader who came across in the third century, or he may have lived centuries later. Some historians place the dates of the kingdom of Dál Riata, or “Dalriada” as it is sometimes known, from the middle of the sixth century. At its greatest extent in the early seventh century it stretched across Scotland’s western seaboard from Skye in the north to Antrim, Ireland in the south with a royal centre at Dunseverick and an ecclesiastical centre at Armoy on the River Bush.

For most of its history Dál Riata was dominated by the Cenél nGabráin dynasty who were based in Kintyre. The first king in all of Scotland whose life is well-enough covered in the sources that we can begin to build a story of his life is King Aedan, son of Gabran. Legend has it that Aedan even went to Iona to be ordained king by the great Saint Columba. He was around forty when in 576 he became king of an area which included parts of southern Argyll and northern Antrim. A century later his people were to be known as the Corcu Reti and by 700 these ‘descendants of Reta’ were one of a number of Gaelic-speaking peoples who were together known as Dál Riata. The founder of this dynasty King Domangart Reti was the son of Fergus, the eldest of the three sons of King Erc who had come across from Ireland, probably from Antrim, Armagh or Down. King Domangart died around 507 and was the father of Gabran and Comgall who established the two kindreds of the Corcu Reti, the Cenél nGabráin in Kintyre and Cenél Comgaill in Cowal.

By 592 Aedan son of Gabran had proved himself in battle, bringing glory and achieving security at home. His powers and prowess continued for many years, and even at the end of his life when he was facing defeats, he still held and ruled over Kintyre and Cowal. He was succeeded by his son Eochaid who ruled for around fifteen years, when he was succeeded by his cousin Connad, ruler of Cowal. For many years the high kingship of the Corcu Reti alternated between the two kindreds. The chronicles indicate a battle in 617 at a place called Fidnach which was probably in Corcu Reti territory. Perhaps Eochaid and Connad led the opposing forces at this battle and Connad emerged as High King. For several years Connad was a successful ruler. In 629 at Ard Corand in Ireland he defeated an army of the Dal Fiatach, the most powerful of the Ultonian kingdoms in Down. After this Connad may even have claimed paramountcy in north-east Ireland as king of the Ulaid. However, two years later at the battle of Fid Euin, Connad was killed. Also killed were Rigullon and Faeble, two of Aedan’s grandsons which suggests that men from Kintrye and Cowal fought together on that day. Connad was succeeded by Domnall Brecc who was defeated several times in battle, in Lorn around 635 and in around 639 at a place called Glend Mureson, possibly by forces from Cowal. Ferchar, son of Connad seems to have succeeded him as king of the Corcu Reti around 638.

The dynasties of Cowal and the British at nearby Alt Clut, or Clyde Rock, seem to have forged an alliance in the middle of the seventh century. The king of Cowal at this time was probably King Finnguine Fota. His son Dargart was the father of two eighth century Pictish kings suggesting an alliance between Cowal and Fortriu, a kingdom of Pictland. Cenél Comgaill long maintained links with the kingdoms of Alt Clut and Fortriu, whose kings were near kin and their support may have enabled King Finnguine of Cowal, and thus Otter, to enjoy great influence in Argyll.

The Scots of Cenél nGabráin were already under pressure in Kintyre by the end of the century finding their dominance challenged by foreign-backed kindreds in Cowal and Skye. The descendant of Gabrain, Máel Dúin and his heirs fought a losing battle for paramountcy in Argyll against foes from Skye and Cowal backed by British and Pictish powers from the South and East. The strongholds of Dunadd and Dundurn were besieged in 682. Following this Máel Dúin was king for another six years, but Finnguine of Cowal was on the rise, backed by Alt Clut and Fortriu. By 690 however, both Máel Dúin and Finnguine were dead. The chroniclers record a great Dalriadan campaign against the Cruithni and the Ulaid in 690 under Máel Dúin’s brother King Domnall Dond the new king. However, from this time the political momentum in Argyll was moving north. The Cenél Loairn kindred, whose name is preserved in Lorne, challenged Corcu Reti supremacy in Argyll and, following a period of confused internecine strife, seem to have secured the kingship of the Region by 700.

The tribe of Cenél Comgaill remained prominent further south in Argyll a generation after the death of King Finnguine Fota, their last known king of any historical significance. Their prominence was probably helped by the fact that King Finnguine’s grandson, King Bridei, was the mightiest king in northern Britain. Argyll at this time was a troubled place of local conflict and between 695 and 702 three Corcu Réti kings were slain and two Cenél Loairn kings to the north toppled. In 710 a battle took place between the people of Comgall and the Picts. It seems the long alliance between the leaders of Alt Clut, Cowal and Fortriu had come to an end. Alt Clut and the Peoples of Cowal seem to have continued cooperation thereafter though.

Interest in the tribe of Cenél Comgaill in the historical chronicles hereafter diminishes, likely reflecting their decreasing power compared to more powerful neighbours. Though occasionally they vied for the Corcu Réti kingship, Argyll often came under the domination of their neighbours. The Pictish king Onuist attacked and conquered Dál Riata in the 730s and 740s. Al Clut may also have taken over parts of Cowal by around 750. For around a hundred years the historical record goes very quiet about Cowal, and therefore the lands of Otter.

We have no surviving written records of Otter exclusively during the time of Dál Riata, though we can imagine the role it would have had. Its location on Loch Fyne between Cowal and mid-Argyll gave it a good position for the movement of goods and people. In these times in Argyll, and for many centuries afterwards, the water would have been a highway for boats and Otter was both right on, and positioned importantly, within this historical highway. In more modern times we know there to have been a ferry here across the loch which gives Otter Ferry its name. No doubt it would have also been an important point of crossing in these very earliest of times. The Bronze Age finds nearby suggest it had long been chosen for habitation. The “oiter” itself, the sandbank promontory, offers one of the best natural harbours in the area. Many of the people of Otter would likely have been fisherman and traders on Loch Fyne and beyond. The records we have of great battles in the area, and the occasions where men from Cowal went further afield to war, such as across the sea to Ireland, are only those instances mentioning them in ancient times which come to us in the chronicles. Warfare would have been a part of life for all, not just during these monumental battles. Who ruled Otter locally under the Cenél Comgaill kings is unknown to us, though it was probably held by one of their trusted chiefs or other members of the Royal Family, not unlike a more modern “Baronage” in general concept.

From around the year 800 Vikings began to raid Dál Riata and by the middle of the ninth century much of Argyll was part of the Kingdom of the Isles, an area of Viking control which covered much of the Scottish coastal areas from the great strongholds of Orkney and Shetland, through the Outer Hebrides, down along what had been the island territories of the kingdom of Dál Riata and down to Mannan, the Isle of Man. The mainland areas of Argyll became part of the new kingdom of Scotland and the name Argyll itself is meant to descend from the Old Gaelic Airer Goidel, meaning ‘the border of the Gaels’. It is thought by some that rather than referring to the sea, the border originally was the border between the mainland Gaelic areas under the King of Scotland, and the islands which were under Viking control.

It was the conquest of the islands of Dál Riata by the Northmen that marks the effective end of their kingdom. The mainland part of Dál Riata not being successfully overrun, such as Cowal and thus Otter, was able to preserve some of the old Gaelic names to pass down to us. The kindreds of Cenél Comgaill and Cenél Loairn give to us the names of Cowal and Lorn for example. It would seem about this time that the relics of Saint Columba were moved away from Iona, either to Kells or Dunkeld. In about 843 Cinaed mac Ailpin, or Kenneth MacAlpin, king of mainly mainland Dál Riata, also became king of Pictland, merging his kingdoms into the unified Kingdom of Alba, or Scotland. Dál Riata was ended and while most of the islands lay with the Vikings, the mainland, including Cowal and Otter, passed into the rule of the new Kingdom of Alba.

Cowal and the Danes

Cowal and Otter remained under the control of the Gaels within the Kingdom of Alba, but “at the edge of two worlds”. The first Viking invaders who had come from the north were the somewhat equivalent of modern day “pirates”, young men looking to fight, loot, sack, and eventually to conquer. They were followed by their families with their belongings, livestock and plans for a new Colony home. Nor were these just one people, some were from what is now Norway and others Denmark and they all came to set up and defend new fiefdoms. In Ireland from around the year 800 came Danish Viking raids on the Gaelic coastline. Over the coming decades they came to stay, first over winter and then for longer, striking out inland as well. These Vikings eventually established the kingdom of Dublin and other strongholds in what is now Ireland and Scotland and sought to expand their power in Ireland and all of the British Isles.

Evidence from many scattered historical written annals tell how one group of Danes attempted to invade Cowal, but were overthrown in their attempt by the Scots and their allies under their King Constantine. The Annals of Ulster say that Danish-Irish kings had invaded other parts of Scotland on a large scale three times in 865, 869 and 904 before they invaded Cowal again in 918. King Reginald, son of Ivar, sought to carve a territory for himself in Argyll to rule and so gathered a great army for this purpose. Reginald at this time was king of the Dubhgalls and with his brother Godfrey and two jarls left Ireland, probably with a fleet assembled at Waterford and Limerick for the purpose. The Scots and their neighbours the northern Saxons set aside their own differences and allied to repel them. It seems that the two forces met at Cowal to fight at Gragava or Garbh-amhain in Glendaruel and at Otter itself on Loch Fyne. Despite the scattered historical evidence we can use a combination of the Irish Annals, local traditions, and landmarks in Cowal and Otter to determine what may have happened.

The great Danish fleet is said to have left their safe harbour in four divisions. In the lead was Godfrey, brother of King Reginald followed by the jarls, a division led by a group of chieftains and then King Reginald himself in the rear. The opposition force, having learnt of the sailing of the Viking forces assembled from Ireland, seems to have assembled themselves further inland in Argyll and then marched to Loch Fyne. They headed to Otter where the Danes had chosen to land. It would have been seen by the Vikings as a perfect spot, where their fleet could rest alongside the sandbank which forms a natural breakwater and on the lee side easily disembark. The Scots and their allies may have expected the Danes to land here given the well known natural harbour and marched there to meet them. The first three parts of the fleet landed there, but it seems that King Reginald coming last saw the army of the Scots on the heights of Otter itself and sailed instead into Loch Ruel where he moored and marched his force to the narrow neck of Glendaruel which is locally known as a result of this battle as “Srath-nan-lochannah”, “the valley or field of the Danes”. This position was likely chosen so that King Reginald could move on the flank or rear of the advancing Scots army towards Otter.

The first three battalions of Vikings divided at Otter and crossed the hill at the end of the district with one half moving to Glendaruel seemingly heading to cut off King Constantine with his reserve from the rest of the Scottish army. They were confronted there by King Constantine and his men who slaughtered them on each side of the river which runs through the glen, therefore giving it its name “Glendaruel”, “ruel” meaning blood. The other half looked to cross the hill at the southern end of what became the Barony of Otter above Kilfinan, and met the main part of the army at a place called “Gleann-a-chatha” or “Glenchow”. A large field in this glen is called “Achaghlinn-a-chata” or “field of the glen of battle” and here the heaviest part of the fighting took place between the Scots, their Allies and the invading Viking army. Next to the field is a ravine through which runs a mountain stream and here is a place called “Leum-an-Lochannaich” or “the Dane’s Leap” where perhaps a Dane fled from his enemies after this great battle at Otter.

There are also old stories in the area of ancient battles which have taken place. In one was told of a Manx hero who after all others had fled about him, found himself with his back to a rock on which he is said to have left an imprint. This rock was until modern times still called “Sgeir-mhanannaich”. At the time of the Irish Viking King Reginald’s invasion, his people either had close ties to, or possessed, the Isle of Man and he may well have recruited part of his fleet there, so perhaps this is where this story originates.

The third part of the Viking force, those men under King Reginald himself, likely worked their way from their landing to attack the Royal Scottish Army from behind. However, it seems King Constantine discovered this ambush and was able to repel the Danes. In retreat, King Reginald possibly made a stand at a place called “Caigean-na-Cruadail,” or “the conflict of valour”. Defeated again, the Viking King Reginald was forced to escape to his ships. In the face of such a significant defeat at Otter and Cowal by the Scottish King and his Allies, it is uncertain how much power King Reginald retained over his followers thereafter, and the Annals of Ulster record that he was slain only a few years afterwards. The mighty Danes, who had conquered so much, including the great fortress of Dumbarton, were defeated among the hills and glens of Otter and Cowal. As a result this Danish dynasty, though remaining strong in their fortresses in Ireland, did not for many years attempt another invasion of the West of Scotland on such a large scale. As such, the lands of the Barony of Otter became a historical turning place for the Royal dynasties and future of Scotland.

The Kingdom of Scots and Kingdom of the Isles

In the 1130s King David went to war with King Stephen of England. His army was in some ways a national one, of men drawn from Lothian, Galloway, Argyll and the north. Their reported warcry was ‘Albannaich’, or ‘Scots’. The Scottish king’s ability to raise these men rested on the cooperation of the Scottish earls who held the right to call the men of their provinces to war. It demonstrated both the King’s power and the Nobility’s desire to work as part of a larger whole. The kingdom of Scotland’s historic roots lay in Argyll as much as in the Tay valley or the country between Stirling and Inverness. The English, Latin and French terms for the land and her people; “Scots”, “Scotia” and “Ecosse” respectively, shows the dominance of the Gaels of Dalriada in the middle ages as these terms replaced the name “Alba” which had more Pictish roots. However, the southern and western Highlands, including the important lordship of Argyll, continued to be closely linked geographically and by their ruling families to the western isles.

It could be said that the history of the West of Scotland from the mid twelfth century to the wars of independence is largely the history of the House of Somerled. Somerled Macgillebrigte was lord or king of Argyll, killed in 1164 while leading an invasion of Scotland through the Firth of Clyde. He claimed descent from an ancient royal lineage of northern Ireland who had acquired a lordship of islands and mountains from Lorn to Tiree, Uist to Kintyre, Islay to the southern Hebrides. Legend has it that Somerled was descended from King Colla Uais, who ruled as High King of Ireland in the fourth century, and was one of the three traditional founders of the Irish kingdom of Airgialla, an over-kingdom of lands around Armagh which they had seized from the Ulaid. It is said that Somerled was descended from him through King Fergus son of Erc, who was also the father of King Domangart Reti, founder of Dál Riata. It is likely that in Somerled’s time the family did not hold all of their lands freely, as the Kings of Scotland and Norway claimed overlordship of parts. King Malcolm IV forced Somerled to come to his peace at Christmas 1160, while Somerled benefited from Norwegian weakness and found himself set against the lords of Man. After his death his lands were divided amongst his four sons. Dubhgall, who was probably the eldest, inherited Lorn, Benderloch, Lismore and Mull. The senior line of his sons were each in turn lords of Argyll or Lorn. They had several castles with their headquarters at Dunstaffnage, north of Oban.

As well as the death of Somerled, the 1160s also saw the consolidation of Scottish royal power, backed by the establishment of crown tenants, in the maritime frontier between Lennox and Cowal, down the Clyde estuary towards Galloway. This westward spread of royal power had begun under King David and by the early 1160s the Clyde’s eastern coast was held from the Scottish crown by great magnates. It is possible that some had begun to look beyond their mainland territories to the Clyde islands and peninsulas of southern Argyll, including Cowal. This encroachment on the House of Somerled’s sphere of influence led to their confrontation with the Scottish crown.

By around 1200 Alan, son of Walter the Stewart, (Steward of Scotland) had acquired Bute and sometime before 1250 his successors had become the lords, or at least the ‘protectors’ of Cowal. This concerned King William, as Bute and the other islands were currently beyond enforceable Scottish royal authority and he was concerned that Alan was building a powerbase outside of his control. Not only this, Alan’s aggressive expansion risked drawing the Scottish kingdom into conflicts in the Kingdom of the Isles. To secure the crown’s power in the area, King William in 1196 gave control of another major west-coast lordship, Cunningham, to his ally Roland of Galloway and built a royal castle at Ayr in 1197 to give him a base for the wider Scottish royal domination of the outer Firth of Clyde.

The building of stone fortresses, often on rocks, islands in lochs, and promontories was a remarkable feature of the barons of Argyll and the islands at this time. These strongholds were a contrast to the earth and timber, motte-and-bailey type that the feudal lords and knights of eastern and lowland Scotland built between c.1100-1250. These castles in Argyll, including Kisimul, Duart, Castle Sween and Skipness, were remarkable strongholds for the time reflecting the fighting which occurred in the area. At the same time as the Noble House of Somerled, there were in Argyll and the isles several lesser families hungry for power and lands, who became lords of their own areas and built these fortresses. In the country east of Loch Fyne, including Cowal, these lands were divided amongst families that traced their ancestry to an earlier period of rule, but began to emerge distinctly during the thirteenth century as more modern powers. Three of them were interrelated and claimed descent from Prince Ánrothán, an eleventh century prince of Ailech or Tir Eoghain. These were the MacSweens, (who married into the royal family of Irish Connacht, the O’Connors), the Lamonts and the MacLachlans. Prince Ánrothán Uí Néill [died c.1080] was of the line of the kings of Ailech, over-kings of north-western Ireland, who in turn descended from historically famous High Kings of Ireland including King Niall Glundubh [died c.920] and the legendary King Niall of the Nine Hostages [died c.450] from whom Princess Afraig [died c.1270], the mother of Cailean Mór, ancestor of the Campbells, is also meant to descend. Prince Ánrothán was the grandson of King Flaithbertach an Trostáin or ‘of the Pilgrim’s staff’ [died c.1036] so called as he had undergone a pilgrimage to Rome. Supposedly after falling out with his elder brother, Prince Ánrothán crossed the Irish sea in the early eleventh century and married an heiress of the Scots’ Cineal Comngall. By around 1200 the MacSweens were the most powerful of his descendants in Argyll and Cowal, holding the lordship of Knapdale and seemingly of Arran too.

The Scottish King William the Lion had generally focussed his attention on England. When he died in 1214 he was succeeded by his son King Alexander II, who enjoyed much better relations with England and turned his attention for Royal control to the west Scottish Highlands and islands. During the 1220s, Alexander moved to assert royal authority in Argyll, raising forces from Lothian and Galloway and sailing from the Firth of Clyde for the purpose. This he probably did via Loch Fyne and Tarbert rather than around the Mull of Kintyre. Many men of Argyll are said to have come to seek peace with the king and pay homage, some and family members of which, the King took as hostages to ensure “good conduct” in future. To consolidate his victory and assertion of Royal power over Cowal, Alexander built a castle at Tarbert at the neck of the peninsula, erected Dumbarton into a royal burgh in 1222, and perhaps formally granted Cowal to the Stewarts as overlords.

Around the same time, a grandson of Somerled called Upsak or Gilleasbuig was given a fleet by King Haakon of Norway and tasked with reclaiming Norwegian overlordship of the Scottish isles and probably Argyll and Kintyre too. He died of wounds in 1230 and his nephew Ewen Duncanson MacDougall was then made lord of Argyll. During the 1240s King Alexander of Scotland attempted to buy peace through purchase of the western islands from King Haakon IV of Norway, but he was refused. At least from 1240 the Scottish king was building up a military following and further assertion of Royal control in Argyll, as there survives a Royal grant of lands in Glassary and Cowal for feudal knight-service to Gilleasbuig MacGilchrist, a kinsman to the Lamonts and MacSweens. This granting will certainly not have been the only one of its kind, although written records at the time are very limited. In response to Haakon’s refusal to sell the islands, King Alexander raised an army and a fleet and sailed into the Firth of Lorn. This force likely contained many men of Argyll, such as from Cowal and Otter which by now were firmly under the influence of the Scottish crown and the overlordship of the Stewarts. The King’s aim was to defeat the House of Somerled, and bring the western isles under Scottish Royal control. When he died on the island of Kerrera at the entrance to Oban Bay in 1249, King Alexander was probably at the point of securing the west Highland mainland and possibly even the islands for the Scottish Crown. His success, and that of his son, King Alexander III, were arguably due to the fact they had adopted the use of the galleys and other ships that were crucial to island conquest so perfected by the Vikings.

Though the Scottish King Alexander II was dead and his plans brought to a halt, the leading Noblemen of Argyll and the western islands must have surely seen the way the wind was turning, and that the Scottish Crown was determined to exert its control. When Ewen MacDougall, descendant of Somerled and formerly lord of Argyll failed in 1250 to have the Manxmen accept him as King of the Isles, and Haakon of Norway chose another over him, this pushed him toward the Kingdom of Scotland. He reconciled himself with the council of lords ruling Scotland on behalf of the minor Alexander III and was accepted as lord of Argyll by them, in return for an annual “ferme” (tithe) of 60 merks. Ewen and his son Alexander proved to be loyal subjects of the Scottish crown thereafter.

When the young King Alexander III took control of Royal government in 1261 almost the first thing he did was to move to continue his father’s work to consolidate his power and control over the western isles. For example, by 1262 the Stewarts had ousted the MacSweens from Knapdale and Arran as well as made other attacks on local powers on behalf of the Scottish king, or at least by his leave. In response, the ageing King Haakon of Norway gathered a fleet of somewhere between one and two hundred ships, gathering them at Shetland then at Skye and down the western seaboard to the Firth of Clyde, taking the castle of Dunaverty on Kintyre and the Isle of Bute in the process. Peace negotiations were opened at Ayr between the two kings but the Scots knew that time was on their side with winter approaching. At the end of September King Haakon moved his fleet close to the Scottish shore at Largs but a westerly gale rose and blew through a whole night and a day with such fury that some ships were dragged across to the mainland where their crews were shot at by Scottish bowmen. The next day King Haakon came ashore himself with a large force of men and gave battle, though they were defeated and forced back to their boats. They withdrew, sailing north but wherever they sent parties ashore for food they were attacked by Scots. The western isles and Shetland and Orkney hadn’t come out decisively for Haakon to fight for continued Norse supremacy. The old Norse king fell ill on Kirkwall in Orkney and died in December.

Haakon’s successor King Magnus, rather than relaunch the campaign, decided to sue for peace and through the Treaty of Perth (1266) leased most of the Kingdom of the Isles to Scotland. After several decades of paying these rents, the temporary arrangement became permanent as ownership. Argyll was united for the first time in four hundred years under a single king, of Scots. It would rise to ascendancy during the next five hundred. In the later thirteenth century the region’s incorporation into the rest of the Scottish kingdom began through Royal pressure and with the acquiescence of the MacDougalls of Argyll, the senior and most powerful branch of Somerled’s kindred who continued to work with the Crown. With this, the process of Norman inspired feudalisation which had already taken place in the rest of Scotland, began to take hold in the west.

The Barony of Otterinverane

In the middle of the thirteenth century five Noble families held Argyll between them, that of Somerled, MacNaughton, MacGregor, as well as the MacSweens and their kin the Lamonts. The MacSweens had possessed the upper half of Kintyre and all Knapdale including lands around Loch Gilp, just across the water from Otter. The Lamonts held Cowal and part of Argyll proper and perhaps Bute as well. The MacSweens, formerly a leading regional power, were during these wars with the Stewarts reduced in their holdings and by 1300 were just one of around a dozen families of equal standing in Argyll. They also lost their stronghold Castle Sween. One of the members of the MacSween family Eoghan, or ‘Ewen’, living in the early to mid-1200s around the time of the troubles with the Stewarts was able to set up a holding of his own at Otter where he built a castle, Castle MacEwen, on a rocky point of the loch at Ardghaddan about a mile below Kilfinan. The establishing of the MacEwen clan at Otter around this time meant they were probably settling in lands that had been held by their cousins, the Lamonts, though as this was next to former MacSween territory the family may have held it beforehand. Cowal was only starting to come under firm Scottish Crown control, and whether Otter had been in MacSween or Lamont hands from this point on it was likely held as a royal grant by the Scottish king.

Eoghan was probably the first MacEwen of Otter but was not necessarily the first baron and it may have been under one of his descendants that the holdings around Otter were reconfigured into a Royal barony. The MacEwen barons of Otter likely succeeded earlier Gaelic chiefs of the area who had held the area independently before Cowal came under the control of the Stewarts and the Scottish Crown. Archaeological excavations have shown there was a prehistoric dun on the site of Castle MacEwen and during the medieval period a palisaded enclosure had been built before being succeeded by a promontory fort enclosed by a timber-laced rampart. Eventually a stone rampart was also added. There is a mound close to Otter House near Castle MacEwen called Dùn Mhic Eoghainn which it is believed was the original site of their baron courts.

By 1300 earlier systems of characteristically feudal landowning such as “thanages” came to be known more commonly as “baronies” and from this time we see baronies identified more clearly in the written records. Many were based around parishes as both the barony and parish were formed on the basis of landowner’s estates. These were fairly cohesive communities with the tenants in a typical barony organising under a Baron and they were disciplined through the barony court, ground their meal at the barony mill, and were served by the barony’s parish church. The neatness of this pattern of Royal control and governance should not be overexaggerated in western Scotland, as not all areas therein were harmoniously or continuously under Royal control in the medieval period. The presence of Castle MacEwen in the south of the parish of Kilfinan suggests that at one time the barony of Otter covered most of the modern parish, meaning the western shoreline of Cowal with Loch Fyne. We know at least that it covered land both north and south of the sandbank at what is now known as Otter Ferry.

In the hundreds of baronies in late medieval Scotland, barons exercised a similar function to Royal sheriffs, though were of a different Noble status. Executing thieves, settling disputes, and upholding Royal government regulations were probably the most common tasks of the barony courts. The baron would have through his court, and his natural position at the head of society, presided over most of the ordinary government and justice. Among the tasks of the baron, along with the sheriff, was the ‘wapinschaws’ or weapon showings, from horses, to armour to swords and spear to select the best warriors. King Robert I developed this further, restricting baronial jurisdiction to estates which the crown permitted to be held ‘in free (privileged) barony’. This reduced their number significantly and concentrated Royal control further. There were over 200 such baronies at the end of his reign, and grants of baronial privileges on this basis proved to be a useful form of crown patronage and control such that they increased to some 350 in number in the later fourteenth century.

When the MacEwens of Loch Fyne established themselves at Otter it is believed they possessed a tract of country about twenty-five miles square and could probably bring out 200 fighting men. This would likely have been little different from the number of fighting men in centuries gone by in Otter and for long into the future. In 1793 a survey was taken of the parish of Kilfinan which is roughly the area the Barony of Otterinverane once covered historically. At this time, there were probably around 300 families and 1400 people residing there. Allowing for women, children, the old and infirm as well as population growth, 200 men of fighting age seems about right for the area.

The Wars of Independence

During the Wars of Independence Argyll became a place contested between the various power factions. An important lord, Alexander of Lorn, was married to a daughter of the Red Comyn and so was allied to the Balliol faction. Alexander and his allies summoned the powerful men of the region to do homage. This included Lamont who held much of Cowal at the time. These Argyll men had previously kept out from the Balliol and Bruce conflict and they could not be compelled by Alexander or his allies to do homage and disregarded the summons of Balliol’s parliament in 1292. Because of this, parliament then divided the area into three, making the Earl of Ross governor of north Argyll, with James the Stewart as governor of Kintyre and Cowal and Alexander of Lorn between them. It seems that the MacDonalds and the Lamonts ignored these governance arrangements and King John’s anger was roused, issuing another warning to them. It is likely the MacEwens here supported their kin the Lamonts in refusing to pay homage to the Scottish King.

The Bruce-Balliol civil war seriously upset the balance of power in the west of Scotland. The MacDougalls, the senior branch of the House of Somerled, were allied to closely to the Comyns through marriage. The Comyns in turn were the staunchest supporters of the Balliols. For their opposition to his rule the MacDougalls found themselves dispossessed of their lands by King Robert the Bruce when he rose to power. Many other leading families of the area also disappeared into history as power wielders for one reason or another during the fourteenth century, including the MacRuaries, Comyns, and Randolphs, and into the void stepped the two most famous Highland families in our present day, the MacDonalds and the Campbells.

The Campbell’s role as Scottish Royal government agents began with King Robert I who granted them territory in the west forfeited by the MacDougalls for their treason, which probably came with the sheriffship of Argyll. The Campbells then, effectively stepped into the place of the MacDougalls as the prominent family of the area by Royal command. However, MacDougall pre-eminence had come in part from their position as the Noble heirs of Somerled, and as the Campbells at the time had no such existing recognized status, they struggled to effectively replace the MacDougalls during the late middle ages. Instead of helping to assimilate the west to the rest of Scotland the Campbell’s acquisition of territories and setting up of cadet branches probably had the opposite effect.

The MacEwens of Otterinverane

Holding Otter as a barony the MacEwens were local lairds. They were also chiefs of their clan. Eoghan had a son called Gillespic who was likely chief at the time of the Wars of Independence and sought to reverse the fortunes of his clan. The aligning of the MacEwens with the Balliol family set them against their old enemies the Stewarts, but also against the Bruce family who claimed and won the Scottish throne. We also know from the written lineage that Gillespic MacEwan had a son Eoghan and that three MacEwen brothers are named in the service of King Edward of England at the time, all probably his sons. A John MacEwen and his two brothers aligned themselves with the English during the wars of Independence, and were granted back the family’s ancestral land of Knapdale by King Edward of England, with dubious practical and highly contested authority to do so at the time, as a result. They had to take back Knapdale by force however, which they may have attempted to do in the 1300s, but ultimately they were unsuccessful, and were subsequently significantly out of favour with the Scottish King Robert the Bruce. One of these MacEwens was likely to have been Eoghan, son of Gillespic. It seems that the MacEwens were forced to accept their losses, and perhaps had their lands even further reduced to an area that just consisted of the remaining barony of Otter. We know that there was a John MacEwen of Otter in the middle of the fourteenth century and he is named as the son of Eoghan and father of Walter. MacEwen legend has it that he and his son Sween were supporters of the powerful Albany Stewarts, Robert Duke of Albany and his son Murdoch. Murdoch and his sons were executed for treason in 1425 however by the Scottish Crown. It is said that this turn of fortune may have been the cause for the yet further downfall of the MacEwen family as regional leaders and landholders under Walter’s son Sween.

Sween is the first person we know named in written records that have been located as baron of Otterinverane per se, and was also the last MacEwen baron of Otter and MacEwen clan chief. Sween has left an uncertain picture to history, and the story behind the loss of the barony of Otter is a part of McEwen folklore, and as such has spawned a number of stories. One tells that Sween was invited by the Campbells of Lochow to their castle at which point they descended on him and his retainers, allowing them to march into Otter and take castle MacEwen unopposed. Another story is that the barony was given by Sween to Duncan Campbell of Lochow in repayment for overdue loans, in which he is sometimes described with a fondness for drink and gambling. While a third version supposes that the loss of the barony was likely due to MacEwen supporting the Albany Stewarts before their downfall. There may be truth in all or none of these tales, however there are some basic facts which can be ascertained. In 1431 Sween granted in a charter to Duncan Campbell, the son of Sir Alexander Campbell and all his other heirs, his lands of Stroynemayte and Barlaggan in the lordship of Otter, for a yearly payment of four shillings. The place of signing, Inverchaolain, was deep in Lamont territory which may indicate that Sween, who was no doubt in some kind of financial trouble, was leasing out part of his lands to his cousins and neighbours the Lamonts at the time. The next we hear is in March 1432 Sween is resigning the Barony of Otterinverane to King James I of Scotland, who regranted it to him in a new charter which stated that if Sween’s male line failed, the lands were to go to Gillespic, the son and heir of Duncan Campbell of Lochow. This is dated March 1432 under the Royal Great Seal of Scotland, and then in June an agreement was entered into at the Otter by Gillespic and Sween and from its terms it appears that the Lord of Otter was married, but had yet to produce an heir. In this complicated indenture it seems to have been agreed that MacEwen would receive from Gillespic Campbell sixty marks and twenty-five cows at Otter, Inchconnell, or Inveraray, or give him the two Larragis and the lands of Killala in the barony of Otter for yearly payment of half a cow. In return, Gillespic Campbell was promised title to the Barony of Otterinverane if MacEwen should die without an heir. It also states that should his heir die before he should have another that the agreement will remain valid, and that Sween MacEwen should give Gillespic Campbell the first offer of the lands, if they were ever to be leased. It appears that Sween did indeed die without an heir, and so his lands passed to the Campbells of Lochow and the MacEwens thereafter became a broken clan, deposed of their lands.

Otterinverane and the Campbells

Sir Duncan Campbell succeeded his father around 1414 and was justiciar and lord lieutenant of the shire of Argyll. Campbell was raised by King James II to be a lord of parliament in 1445 as Lord Campbell. The lords of parliament emerged in the Scottish peerage at this time, with a section of the higher nobility elevated to this new rank. These lords of parliament copied the English parliamentary barons in their naming systems and right to summonses to parliament. This institutionalised the higher nobility into an easily identifiable group, the lords rather than the ‘lairds’. In the highly status-conscious fifteenth century, Scottish feudal barons who were of the highest rank below dukes and earls and who were accustomed to having a voice in the country and in parliaments seem to have wanted some way of distinguishing themselves from the lesser barons below them. The pressure for this comes from at least the 1410s, though by the 1440s so many earldoms had disappeared there seems to have been a political and social vacuum. At this time most of the important nobles were greater feudal barons, holding several feudal baronies, so it made sense to award these people a new title ‘lord of parliament’. In many places by the late fifteenth century the trend was to split up individual feudal baronies and elsewhere amalgamate them and also to create new ones so that the territorial patterns of lordship were growing increasingly complex. The Scottish baronial system continued to work and remained in place because most crime and disputes were local, between neighbours, and so because the barony was one ‘unit’ like a parish the barony courts were able to deal with most cases and therefore they continued to be useful for governance.

Lord Campbell was a great religious benefactor, including donations to the monks of the abbacy of Sandale, in Kintyre, and founding the collegiate church of Kilmun in 1442. After the college of Kilmun was endowed, the Campbells got a firm footing in Cowal and between then and the Reformation they became paramount there. Having consolidated their hold over Cowal the Campbells were in a much stronger position in Argyll and when they were made earls they began to enter the national stage.

Lord Campbell was succeeded by his grandson Colin who like him was in high favour with Scottish King James II who made him Earl of Argyll in 1457. He held various domestic and foreign appointments for King James III including master of his household, lord justiciary south of the Forth, commissioner and ambassador many times to England and eventually lord chancellor in 1484. He was in England on Royal business in 1488 when the Scottish King was slain at the battle of Sauchieburn, and he was again appointed lord chancellor by the new King James IV. His son Archibald, 2nd Earl of Argyll was also in high favour with King James IV who made him lord chancellor of Scotland in 1494 and later chamberlain and master of the household. In 1493 the annual ferme (royal tithing) of Otter was 30 marks, slightly larger than some others such as Kilmun at 24 and a half marks but smaller than many others such as Glassary with 50 marks. In 1481 and 1494 an Archibald Campbell of Otter appears in record, and so as was becoming the custom of the Campbells of Lochow, now the Earls of Argyll, the lands of Otter were held by another extended family of Campbells as clients. In 1501 Archibald, Earl of Argyll granted to Duncan, the natural son of Colin Campbell of Otter, ‘the 40 marklands of Otter and the stewardry of the same.’ Argyll commanded the vanguard of the king’s army at Flodden field in September 1513, where he is said to have shown remarkable valour. He was killed during the battle along with the Scottish King and the flower of the Scottish nobility.

King James V confirmed the barony of Otterinverane to Colin Campbell, 3rd Earl of Argyll and in January 1525, his son, Archibald Campbell received a Royal Charter of all his father’s lands which the Earl had resigned for regrant to him by the King, including the ‘Barony of Otter.’ The 3rd Earl was appointed one of the four counsellors to King James V in 1525. During his life Argyll held many important positions including lord lieutenant of the borders, warden of the marches, heritable sheriff of Argyllshire, justice general of Scotland, and master of the king’s household. His son Archibald, 4th Earl of Argyll continued in the tradition of his family as a well-valued servant to the royal house of Stuart and he was made temporary regent in 1536 in the absence of King James V. During his tenure in 1541 the lands and barony of Otter were incorporated into the barony of Lochow through a charter granted by James V. In October the following year, James granted Archibald Campbell, son and heir apparent of Archibald Campbell the lands and barony of Lochow, the lands and barony of Tarbert, the lands and barony of Otterinverane– all incorporated into the barony of Lochow for administration.

The 4th Earl was one of the nobles who opposed the match between Queen Mary and King Edward VI of England and when war broke out with England in 1547 Argyll distinguished himself at the battle of Pinkie and the siege of Haddington. He was among the first of the Scottish nobles to embrace the Protestant religion and worked to bring about a Reformation in the Scottish Kirk (church). He was succeeded by his son Archibald, 5th Earl of Argyll who was also a firm supporter of the new Protestant religion. In 1559 he went to France to seek Queen Mary’s support for it and upon returning entered into an association with the Earls of Glencairn and Morton and together they had the Reformation formally established in Scotland by 1560. Upon the outbreak of civil war in Scotland, Argyll supported the Queen and was general of her forces at the battle of Langside in 1568. His troops were routed but he remained loyal and when the Queen was made prisoner in England she nominated him as one of her regents. Arygll eventually accepted the authority of King James VI, becoming a member of his privy council in 1571 and later justice general, keeper of the great seal, and lord high chancellor of Scotland.

In the sixteenth century there were over a thousand recognized Scottish feudal baronies, though these were more fragmented than in previous years. In the early modern period the properties of landowners would usually form one or more baronies and within the barony the baron court gave the landowner further authority. Baronies, with their baron courts, were basic units of rural society by this time. They were then single entities, originally created by royal grant, bonding together the law and practice of a particular area, though not always geographically continuous. A baron court had criminal powers, though these did not extend to pleas of the crown, i.e. major offences. In practice in the seventeenth century they confined themselves to minor matters but this is not to say that they were unimportant. Most legal needs of the people were minor affairs. Petty thefts, encroachments and minor acts of aggression, and of course encroachments on the rights of the baron, formed most of the regular business of such baron’s court, with penalties usually of fines but sometimes forfeiture. Baron courts met at the instance of the baron, when business had accumulated, and the baron might or might not choose to preside in person. There were also the ‘‘birlaymen’’ who might be chosen by the baron or elected by the court. In either case they would be men of considerable local knowledge, who would settle local issues and divide local burdens. These men were possibly the remnant of a previous system when local people had policed themselves. Baron courts spent much of their time on local policing, such as over verbal or physical abuse and protecting the land, such as the burning of moors, polluting rivers, or cutting down green timber. The court could also enforce the payment of rents or service in kind, as well as supervising the maintenance of the mill, extraction of teinds, and other business such as issues caused by straying animals.

When the 5th Earl of Argyll died without heirs he was succeeded by his brother Colin as 6th Earl of Argyll in his titles and lands, including Otterinverane. He was made a privy councillor to King James VI in 1577 and lord high chancellor in 1579. In September 1580, King James granted Archibald Campbell, son and heir apparent of Colin Campbell, 6th Earl of Argyll, the lands and barony of Lochow, the lands and barony of Glenurchy, the lands and barony of Over Cowal, the lands and barony of Otterinverane, the lands and barony of Tarbert as well as other lands and baronies. Archibald, 7th Earl of Argyll known as ‘the Grim’ was commander of the forces sent against the Earls of Huntly and Errol at the battle of Glenliver in 1594 and though defeated, it is said that he showed great courage. Argyll’s later military career was more successful. He suppressed a legendary insurrection of the McGregors in 1603, and an even more formidable one of the McDonalds in the Western Isles in 1614, for which he was granted Kintyre and made hereditable commissary of the isles. In March 1610, King James granted Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll the lands and barony of Otterinverane and others all incorporated into the free county, lordship and barony of Argyll for governance. In 1618 he went to Spain and after converting to Catholicism, entered the service of the Spanish King and distinguished himself against the states of Holland, assisting in the military taking of several places of strength. His son Archibald succeeded him in Scotland under the rule of the Scottish King. He was a privy councillor to King Charles I and made Marquis of Argyll in November 1641, however he was a firm supporter of Presbyterian church government and was a leader of the Covenanting movement against the Scottish King during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638-51. Active in the fighting, Argyll raised a regiment for service in Ulster, Ireland, and in 1644 he led the Scottish army into England before returning to quell a Royalist rising by the Marquess of Montrose in the Highlands, dashing the hopes of the King in Scotland. As the fortunes of the country changed, Argyll supported King Charles II, placing the crown on his head in his Scottish coronation in 1650, but he then supported the Commonwealth and Protectorate and upon the Restoration of the monarchy he was executed for treason and all of his estates and titles were forfeit, including the Barony of Otterinverane.

Argyll’s son Archibald had been a firm supporter of King Charles II during the wars, and in 1654 he was imprisoned, though he later agreed to submit to the new regime and was permitted to live privately. With the Restoration, though his father was executed, Argyll was granted back the lands and titles of his family, and in October 1667 a Crown Charter was issued confirming on the new Earl of Argyll various properties including the lands and the Barony of Otterinverane. He was later made a member of the privy council, and a commissioner of the treasury in Scotland.

During this period the extended Campbell family stewards of Otter had proved to be efficient in their duties. In July 1587, the Act of Parliament for ‘the quieting and keeping in obedience of the disordered subjects and inhabitants of the Borders, Highlands and Isles’ named a Laird of the Otter, who must have been Archibald Campbell, the steward of the Otter at that time. Another Archibald Campbell of Otter was named in 1643 as one of colonels of horse of foot for Argyll by the Act for the Committees of War in Shires. In 1662 the laird of Otter, was among a list of those in the country to pay a sum of money to the King, of which he offered £2000, a significant sum. A signature of the lands of Otterinverane was granted to Colin Campbell and in March 1678, this Colin Campbell of Otter was one of the men from Argyll named in the 1678 granting of money to Charles II for the upkeep of the army.

In 1685 the ascension of the Catholic James VII raised concerns among the Protestants in his Kingdoms of England and Scotland and as a result two rebellions were organised in tandem, Monmouth’s Rebellion in England and Argyll’s Rising in Scotland. Like his forbears Argyll was a firm Protestant and when the Test Act was passed he refused to swear to it on grounds of conscience and was sentenced to death. However, he escaped to Holland, and upon the accession of King James he raised men and invaded Scotland where he rallied his Clan to his cause, including certain of the men of Cowal and Otter. Both Rebellions were crushed and the Dukes of Monmouth and Argyll and many of their followers were executed. In the aftermath of this many of the Argyll lands were once again forfeit to the crown and Alexander Campbell of Otter is named one of those in 1686 whose lands ‘fell in his Majesty’s hands by the forfeiture of the forenamed persons.’ The Barony of Otterinverane and its governance was given by King James to Alexander Maclean, a son of the Bishop of Argyll. He was knighted shortly afterwards to be known in history as “Sir Alexander Maclean of Otter”. Sir Alexander was a faithful follower of Sir John MacLean, a leading Jacobite of the ’88 and the ’15 uprisings. Sir Alexander Maclean of Otter himself led a battalion at Killiecrankie where he was severely wounded and with the failure of the Rising, he entered French service becoming a lieutenant-colonel under the French Royal banner.

Archibald Campbell, son of the Earl of Argyll, had allied himself with William of Orange in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution, and was one of the commissioners sent to London by the nobility and gentry of Scotland to offer the crown in the name of the convention of estates, to the prince and princess of Orange. With the fall of King James VII, the Earls of Argyll were restored to favour and in 1690, the Scottish Parliament passed an act rescinding the forfeitures which had taken place under the Restoration Stuart regime, which included to Alexander Campbell of Otter as the client of the Earl of Argyll. Lord Argyll was admitted to the privy council in 1689, became a lord of the treasury in 1690 and a colonel of the Scotch horse guards. In December 1690 Archibald Campbell was served heir to his father the Earl of Argyll, in the lands and Barony of Otterinverane, along with many other baronies. Archibald Campbell the 10th Earl of Argyll was rewarded in 1701 with a Dukedom for his service to the crown, especially during the Glorious Revolution where he had raised a Regiment of Foot and took part in the pacification of the Highlands, including by order of the Crown the infamous Massacre of Glencoe.

Argyll was succeeded by his son John as the 2nd Duke of Argyll. Early in his career he had distinguished himself on the Continent with the command of a regiment of foot and at many sieges and battles including at Malplaquet. Argyll around this time was made one of the extraordinary lords of session, high commissioner to the parliament of Scotland, baron of Chatham, Earl of Greenwich, governor of Minorca and one of the privy council. In great favour with the new Hanoverian monarchy he was made commander-in-chief of all the forces in North Britain. In a ‘Resolve’ drawn up by the lairds of Argyll in the face of a further Jacobite invasion in 1715 is named John Campbell of Otter, the steward of the Earls of Argyll, who promised to raise men in defence of King George. During the ’15 Rising as commander-in-chief Argyll marched out from Stirling to oppose the forces of the Earl of Mar, meeting at Sheriffmuir where he secured a famous victory which led to the collapse of the Rising. Afterwards he was made lord steward of the household, raised to be Duke of Greenwich, field-marshal of Great Britain and sat in the House of Lords. These actions confirmed the ascent of the Campbells of Lochow to the elite of the new British aristocracy and they moved beyond Scottish political life to become one of the leading families of Empire.

The 2nd Duke of Argyll died without heirs and was succeeded by his brother Archibald. He had begun his studies to be a lawyer but upon his father becoming Duke he entered the military before a career as a statesman including sitting in Parliament and in 1706 he was nominated one of the commissioners for the treaty of union and was made Earl of Islay for his service. In 1708 Islay was made an extraordinary lord of session and was one of the sixteen peers for the first British parliament, before becoming justice-general of Scotland and being called to the privy council. With the Rising of 1715 he re-joined the army and served in the West Highlands, before joining his brother at Stirling. From 1725 to 1734 as privy seal he ran Scottish affairs. He too died without heirs and passed his lands and titles to his cousin, John Campbell of Mamore. Mamore had like his cousins joined the army and in the ’15 Rising served as aid-de-camp to the 2nd Duke of Argyll and in the ’45 he commanded the army in the west of Scotland. He was a brigadier-general at the battle of Dettingen in 1743 against the French and after fighting in Flanders and Germany was raised to be lieutenant-general. He was groom of the bedchamber to the Prince of Wales and continued to be so during the whole of his reign. He and his father represented Dumbarton in every parliament since the Union but in succeeding to the estate and honours of Argyll the Duke was instead elected one of the sixteen peers for Scotland. He was succeeded by his son John as 5th Duke of Argyll who had also joined the army and served on the Continent before a long career at home, including during the ’45 Rising. For many years he was commander-in-chief of the forces in Scotland and later was made field marshal. He sat in Parliament for Glasgow 1744-61 and later for Dover. Upon succeeding to the family estates, he took great interest in agriculture and was elected first President of the Highland Society.

Modern Otterinverane

At this time the Barony of Otterinverane had ceased to be what it once was, a pivotal part of local society and Argyll history, as the role of both the Campbells of Argyll and the world around them changed. This was the case across Scotland, and while baronies had for centuries been central parts of local law and order, by the eighteenth century this was no longer true. In 1794, the Reverend Alexander McFarlane in his Statistical Account of the parish of Kilfinnan wrote that;

On a rocky point, on the coast of Lochfine, about a mile below the church, is to be seen the vestige of a building called Caisteal Mbic Eobbuin, i.e. M’Ewen’s Castle. It was a wide, but irregular building, neither square nor circular, perhaps nearer a pentagon than any other plan: it does not appear to have been built with any kind of mortar; but, from the quantity of rubbish, it must have been of a considerable height. This M’Ewen was the chief of a clan, and proprietor of the northern division of the parish [of Kilfinan], called Otter. His possession of it must have been of very remote antiquity; for there is no record nor tradition that says who possessed the property before them. Many of the clan still reside upon the estate… [Otter] is also a Gaelic word, descriptive of a shallow place, over which runs a gentle current; and accordingly this division of the parish is so called from a most beautiful sand bank, which juts out into Lochfine, in a serpentine form, near the seat of Mr. Campbell of Otter, proprietor of the whole division but one farm. This bank is 1800 yards long, from water-mark to its remotest extremity at low water, and forms, with the land on the S side, an oblique, and on the N. an obtuse angle. In time of spring tides, it is entirely covered at high-water, and about 3 hours after the turn of the tide, the whole appears to within a few yards of its extremity; and from its length, narrowness, and form, makes a very uncommon and pleasant appearance. It seems to be an encroachment of the sea upon the land, which, from its nature, could give it little opposition, being low, level, and channelly. On the N. side of the bank, where seems to have been the ancient channel of the loch, the water is very deep: on the S. side, where, according to conjecture, the surface has been peeled off by the united force of storms, and a strong current, it is very shallow; ebbs a great way out in time of spring tides, and gives opportunity to the inhabitants in the neighbourhood to gather oysters, spout fish, mussels, and other various kinds of the shell fish, which are there to be found in great perfection and abundance… There is pretty good anchorage also at the ferry of Otter, already mentioned, although not so well sheltered as the Kyles of Bute. Ferries. There are 3 ferries; one, already mentioned, at Otter, near the N. end of the parish, across Loch- fine to the parish of Kilmichael, in the district of Argyll. At this ferry, the loch is supposed to be near a league broad, and the fare is 3 d. Sterling each man; 9 d. each horse. It is badly attended on either side as to hands and boats; and at the inns very ordinary accommodation is to be had, when the traveller happens to be storm-staid. This is very surprising, and much to be regretted, as it is very much frequented, being on the very public line of road from all that part of Argyllshire lying on the N. W. side of Lochfine, to Cowal, Greenock, Port-Glasgow, and all the adjacent parts of the Low Country.’

The Campbells had moved far beyond just Argyll in their thoughts and deeds. George William Campbell, 6th Duke of Argyll was a Whig politician and sat in parliament for St. Germains in Cornwall from 1790-6 and in 1807 as Duke of Argyll was appointed vice-admiral of western Scotland. He became lord steward of the household and member of the privy council in 1833 though he died without issue and was succeeded by his brother John as 7th Duke of Argyll. After joining the army the Duke served in the Low Countries during the Revolutionary War with France and was later made colonel of the Argyll and Bute Militia. He represented Argyllshire in Parliament from 1799-1822 and was a Fellow of the Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh. He was succeeded by his son George, 8th Duke of Argyll. A Whig politician in the tradition of his family, from 1852 to 1881 whenever the Liberal party were in power he was a member of the Cabinet including as Lord Privy Seal, Postmaster-General and Secretary of State for India and as a privy councillor. Argyll later opposed Home Rule and broke with the Liberal Party. He was very concerned with the Kirk and later in life ensured the ancient cathedral on Iona was secured by the Church of Scotland. He published many books, mainly on philosophy and political economy. In 1892 he was made Duke of Argyll in the peerage of the United Kingdom. In the late nineteenth century Brown in his Memorials of Argyleshire wrote about the ‘great sandbank’ which juts out more than halfway across the Loch and is dry at half-tide with an area the side of ‘an ordinary country road’. Apparently, ‘its formation is so peculiar that the district takes its name from it- ‘Oitir’’.

John, 9th Duke of Argyll was a Liberal and then Liberal Unionist politician and Member of Parliament for Argyllshire from 1868-78 and Manchester from 1895-1900. He was made privy councillor and from 1878-83 was Governor-General of Canada. He succeeded his father as Duke of Argyll in both the peerages of Scotland and the United Kingdom, as his successors continue to do. In 1871 he married Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria. He was succeeded by his nephew Niall Diarmid Campbell as 10th Duke of Argyll. He studied at Oxford and was admitted to Middle Temple but after succeeding his uncle to the family estates he withdrew from his career as a lawyer. From 1923 to his death he was Lord Lieutenant of Argyllshire. He never married and was in turn succeeded by his cousin Ian a great-grandson of the 8th Duke. His mother was American, and he was educated in Massachusetts and then Oxford. As a captain in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders he served during the Second World War where he was taken prisoner. He was succeeded by his son Ian as 12th Duke of Argyll. Educated in Switzerland, Scotland and at McGill University in Canada he served as a captain in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of which he later became Honorary Colonel. Argyll was a sales executive and the Director of several distillery companies including Campbell, Aberlour Glenlivet and White Heather. He was succeeded by his son Torquhil, 13th Duke of Argyll. He attended the Royal Agricultural College and was a Page of Honour to Queen Elizabeth II. He is a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Distillers and a Freeman of the City of London.

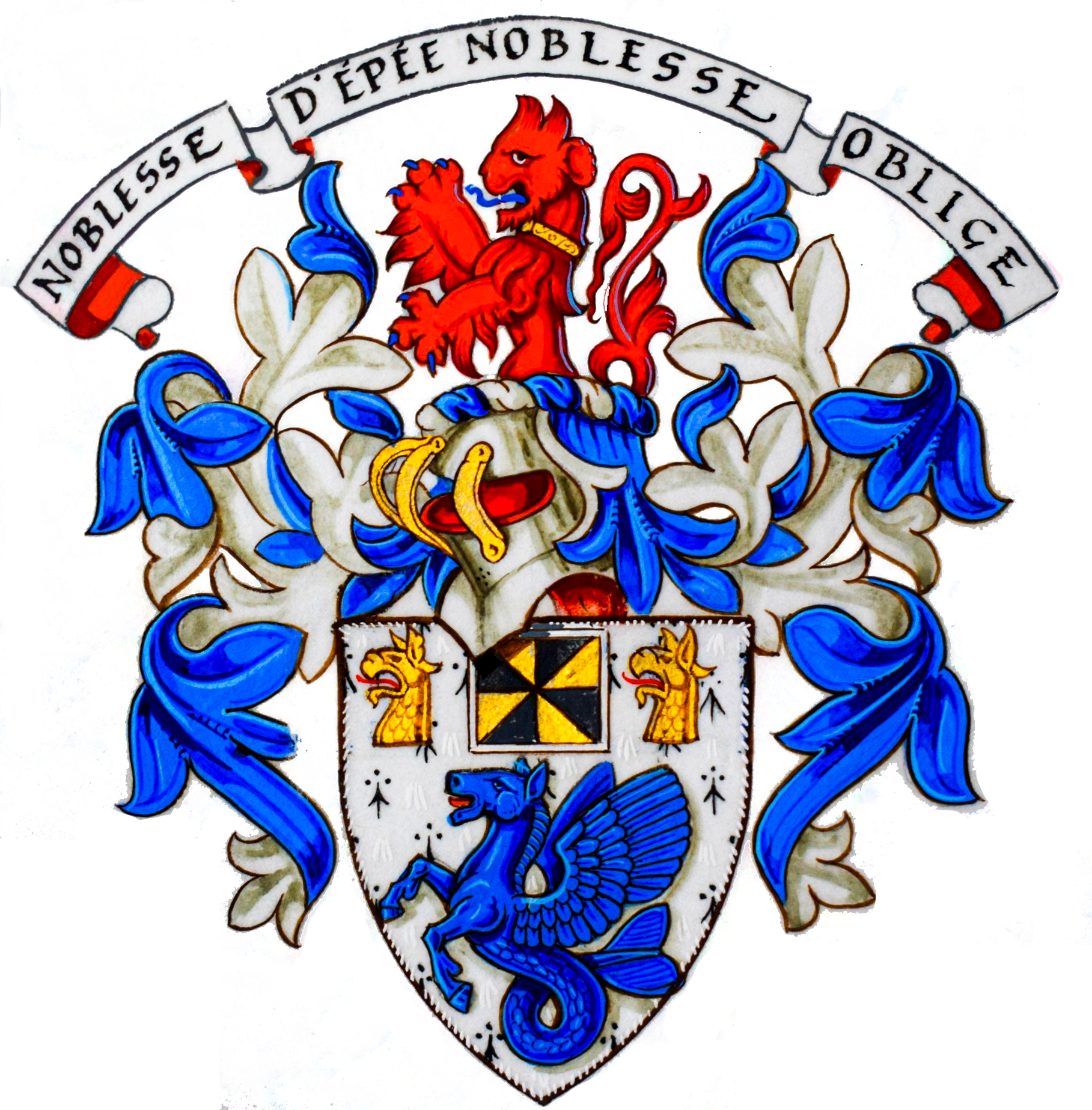

Assoc. Professor Sean Lambert Collin, Esq., Barrister, Solicitor & Attorney, succeeded to the Barony of Otterinverane through assignation from his Clan Chief, the 13th Duke of Argyll on 8th July 2019. He descends directly in multiple paternal and maternal family lines from 175 prior individual Baronial Titleholders of the Barony of Otterinverane, and shares common family ancestry with all other prior historical Barons of the Barony. Through his own lineal Family ancestral descent, he thus keeps the Barony of Otterinverane within contiguous extended Family holding since at least the 13th century, and is the 31st member of such Family to hold its title of “Baron”. He is married to Ambassador Yvette Running Horse Collin PhD. The Baroness paternally descends from Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll, and 9th Baron of Otterinverane.